Which Side Are You On?

Timely news, a fresh video, and a candid conversation with pianist and composer Conrad Tao about current projects, political imperatives, and doing ethical work in a field bound by custom and class.

Here Is the News

Friday, July 3, is the latest Bandcamp fees-waived sale day, when the popular platform will cede its standard cut of all sales for 24 hours, starting at midnight Pacific time, in order to benefit artists and indie labels whose income has been impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. (As of now, this is the last such sales event the company has announced.) In addition, many artists and labels are donating some or all of their cut to a wide variety of charitable pursuits. Check out this useful list of donations, deals, and special merch available today… and if you need help figuring out time zones, isitbandcampfriday.com is here for you.

In one of last week’s newsletters, I tipped my virtual cap to the industrious writer Joshua Minsoo Kim, whose interviews for his Substack publication Tone Glow go from strength to strength. (The newest issue, with its collaborative list of favorite albums issued from April to June of this year, is a must.) This week, Kim returned the favor, generously mentioning Night After Night in a revealing interview that appeared in yet another imperative Substack newsletter: Music Journalism Insider, written and published by Todd L. Burns. Thanks, Joshua… and no, Todd, I’ve not forgotten that I owe you an email.

In a sad yet entirely anticipated development, Time:Spans, the ambitious new-music festival mounted annually in New York City by the Earle Brown Music Foundation, has announced the cancellation of its 2020 live presentation, which was to have taken place at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music in August. Instead, the series is headed online, with several planned participants – including Juliet Fraser, Quatuor Bozzini, the International Contemporary Ensemble, Sō Percussion, JACK Quartet, and Yarn/Wire – creating new videos for the occasion. Watch for further details and sign up for the mailing list here.

Video of the Week

New York City’s Argento New Music Project, for 20 years one of the city’s premier presenters of contemporary classical music, has been posting videos regularly during the present pandemic, including interviews with composer collaborators and unique performance clips, like a delightful account of Steve Reich’s New York Counterpoint that showcases the brilliant Irish clarinetist Carol McGonnell in an 11-part virtual chorus. McGonnell is also featured in the project’s newest offering: Flicker, a brief composition by Michel Galante, Argento’s founder and conductor, and McGonnell’s husband. Customarily in such pairings, the clarinet flits and flutters over the piano’s support; the way McGonnell and Galante flip the script has to be seen to be believed.

Interview: Conrad Tao

The second Bang on a Can Marathon presented online during this time-suspended summer season, which occupied six or so hours of screen time on June 14, included a customarily star-studded roster of groundbreaking artists: from Rhiannon Giddens to Terry Riley, with numerous noteworthy compositions and performances in between. The segment that stopped me in my tracks above all else, though, was that of Conrad Tao, a pianist and composer who for years now has juxtaposed and combined styles, eras, and musicians in ways that constructively interrogate the canon and convention.

When his characteristically busy schedule was halted by the pandemic, Tao swiftly shifted his productivity online. I’d already seen him perform Frederic Rzewski’s The People United Will Never Be Defeated! in a livestream event produced by the 92nd Street Y in March. Rzewski also provided the music Tao played for his Bang on a Can set. He prefaced a rousing account of Which Side Are You On? with a vintage recording by Florence Reece, who wrote the original protest song on which Rzewski’s composition is based, and a snatch of a fiery recent version by Rebel Diaz with Dead Prez.

On June 19, when the music-sales platform Bandcamp donated its share of all sales to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Tao and his colleagues in Junction Trio – violinist Stefan Jackiw and cellist Jay Campbell – released their debut recording, featuring music by Dvořák, Ives, and Christopher Trapani, and directed the money they made toward abolitionist initiatives. And in addition to his piano performances, Tao has also begun to create short video works during quarantine: one in response to a commission from the Guggenheim Museum, and another for an online festival produced in June by the up-and-coming Brooklyn organization ChamberQUEER.

More online concerts loom ahead in August, by which time Tao no doubt will have produced even more unanticipated art. During a recent interview conducted via FaceTime from our respective apartments, he discussed the work he’s pursued in isolation, the impact recent protests have had on his life and art, and the need for drastic, fundamental change in the classical music industry. (The interview was edited for clarity and length.)

STEVE SMITH: You’ve managed to be very productive during this unusual and strenuous period of time, and I’d like to talk about the work you’re making now—but of course, we have to address it in the context of everything else that’s been going on in the world. So the place I’d like to start is simply by asking how you’re doing. How are you feeling, these days? How are you coping with this interminable isolation?

CONRAD TAO: It’s been great, actually. There’s so many new dimensions of shame and guilt that emerge in a new experience like this, and in the early weeks, every time I took a walk, there was this miasma of anxiety. I had to get over that, this weird guilt and anxiety around just living your life, essentially. That was an interesting experience. And then, I never once felt pressure to be productive. If anything, I felt the opposite. I really didn’t want to be a scab, but the truth of the matter is, left to my own devices, I would just endlessly make stuff and put it all out there for free. So I had to get over my anxiety around that and really think through it.

In terms of the actual creative work, it’s been really interesting. The question of why we do what we do, why we make music, why we put it out there for people in the absence of clear external containers in which to do so: that’s been a really productive question. And it’s activated other parts of my mind. I always used to think, if I wasn’t a musician, I would probably want to be a video editor and a filmmaker; okay, well, now I literally have to learn to do some of that. So for me, this period has ended up being about opening new windows of creative possibility. And then in the last three-and-a-half weeks or so, I’ve felt so invigorated. This is the least powerless I’ve felt in years. I’ve been out a couple of times so far, and it’s amazing; the energy out there is really incredible.

When you say you’ve been out, do you mean….

I mean the protests and marches.

That’s specifically what I wondered.

I’ve been really inspired by them, and I feel a real resonance with everyone who’s out there. It’s a rebellion that’s being led by young people I feel a close identification with. I was talking about this with Jay Campbell, and he made the point, which really resonated with me, that when you’re an angry leftist, you sometimes feel crazy. You sometimes feel like you’re the angriest person in the room, and other people just aren’t paying attention. And for me, at least after a while, I started wondering: am I just deranged? [laughs]

So to see that, no, there are plenty of people who are actually all really pissed off and recognize the power of that… I realized a while ago that I wanted to honor my anger. I wanted to honor my rage. I wanted to advocate for rage as a potentially productive thing. So I feel very galvanized by this moment, and I’m grateful that I get to experience in person the ecstatic feeling of possibility when everyone is raging together.

It’s been a pretty incredible time. It’s also like, thank God we’re living in actual history, instead of suffering through some eternal present that we can only keep tinkering with. It’s really exciting to finally feel some of that possibility. It’s scary, too…

So then, you feel like there is genuine actual change being implemented?

Not implemented. Definitely not implemented. But I will say that this feels different. It feels more like a rainbow coalition. Something that I think has emerged, something that I share personally, is I think there’s sort of a mass aesthetic revulsion emerging, a revulsion at the symbolic, placating, “reform is incremental” aesthetic. I think about something like the Congressional Black Caucus giving the House Dems kente stoles. I understand that, as a CBC gesture towards unity; that doesn’t mean that I think it’s a smart decision.

And also, it’s just like: why? None of this means anything. The so-called “Justice in Policing Act” looks nice on paper, but it’s toothless, repeats failed reforms tried elsewhere, and it’s not what we're asking for. I don't know if you saw the video of the mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, getting shamed off the street by protesters? It’s astonishing. It’s this incredible moment where you realize: maybe we have the ability to make elected officials afraid of the people that they’re supposed to represent. And this is a slow shift, because there’s still folks who don't share that sensibility, who are scared of it. It has this aesthetic element, but it’s rooted in concrete, materialist analysis, where the reason for the aesthetic revulsion is the lack of actual substance.

We have felt this rage previously. We’ve been here before. But, as you said, something does feel different, and it is being led by a youth coalition that's not afraid of speaking out. You mentioned Jay Campbell—the ways in which he’s used the JACK Quartet Instagram to speak out is something you wouldn’t have expected from an earlier generation. In the context of all of this, how do you then view the Title VII decision the Supreme Court just handed down? With trepidation, joy, skepticism?

I hold it with complexity. On the one hand, it is a victory in practical terms. But the logic behind the ruling is kind of mind-bending and worth chewing on. It’s a matter of interpretation; it’s still an argument about textualism. Plus, friends who are queer activists, and specifically labor activists, have made the point that our next fight is ending at-will employment. That would be a smart tactic, actually, because it points our next fight toward something much more broad. If we could find a way to change the terms about at-will employment, so that the onus is on an employer to provide a reason for firing, then that has implications beyond just one socially defined category. And that has greater potential for liberation.

So, you know, you acknowledge, you take the good news, you think about it critically. You just try to maintain that multi-dimensionality, moving forward.

So then, I’m not asking you to offer a prescription for an entire discipline or industry, but I do wonder how we bring these issues fruitfully and powerfully into the artistic realm?

I don’t know if we can. I mean, I guess I should be more specific: I’m not sure if you can unless there’s actual concrete investment and restructuring. I don’t envy people in power at cultural institutions, because it’s a challenging bind that they find themselves in. It’s kind of funny to observe things that I’d mulled over a long time ago individually happening at an institutional level. What’s surprising to me is how many folks genuinely didn’t engage with the basic fact that the institution of classical music historically has upheld white supremacy. In order to feel like I could continue doing this, a few years ago I had to try to think through some of those contradictions and challenges. My perspective on it as a musician has always been that these institutions, and the structures of knowledge that justify them, uphold white supremacy—and yet, I love this music.

That’s right.

Right? I love this music, and I would like to think – and this may be a little hubristic – I would like to think that the possibility is by maintaining that critique, and really thinking about it a lot, and trying to center it in the work somehow, even if it’s only known to me, that somehow I can prove that people who subscribe to this preexisting structure of knowledge to provide all of the terms of valuation are missing the fucking point, or are not listening to the music to its full capacity. I bring to that my experiences with conservatory culture, and again, I try to be honest about what I learned from that time and what I also now really think is wrongheaded.

So I guess all of that’s to say that I don’t know if we can meaningfully bring things into our field yet, because right now we seem to only be able to think within our institutional reality. We really should think and act at a basic human level right now.

Let’s talk then about some of the expressions of that outlook that you’ve put out into the world recently. On June 5, which was a Bandcamp sale day, you put out the first Junction Trio recording. How did the three of you come to the decision to make that offering?

We had initially hoped to release some of those recordings, most of which were from a performance last summer… we were looking to do a fundraiser early on for COVID artist relief funds. But because emails are emails, we didn’t end up getting files until just a few weeks ago. And once those files came in, and suddenly there was a new and extremely urgent effort that I knew I wanted to provide material support to, I proposed it in a group text. I took the initiative to find organizations to donate to, and we discussed it among ourselves.

It was Jay’s idea to match the money raised, which we all were very enthusiastic about. Once we realized that we could each individually be willing to match, we realized we could really make people’s dollars go further. I put out a call on Twitter, and reached out to some friends privately, for abolitionist organizations in New York on the ground who were and are doing vital, immediate work.

And then we got going, and it was really amazing—and in fact, it was one of those lesson-learning moments, too, where at some point I kept updating the boys on where our numbers were at, and one of us had to say, sorry, but I have to actually max out at $1,750. It was simultaneously a learning moment – ohhh, this is why people put ceilings on their match pledges – but also, what a nice problem to have.

Right, exactly.

Also, because I shared it on social media, and because of the vast array of people who are engaged with that content, I ended up a friend who wished to remain anonymous also committing to a match. So we ended up being able to match people’s donations by 500 percent. Once all of that was accounted for, we ended up raising $14,500, which was split between three organizations, one of which was Freedom Arts Movement, which is an artist-led collective that was doing street medic work and providing supplies on the ground. One was a donation to Survived & Punished, which is an organization working to decriminalize survival of domestic violence and gender violence—this was the New York chapter of Survived & Punished, which is a nationwide coalition, and they were doing a commissary fundraiser. And then we donated the other third to the Emergency Release Fund, which is a bail fund that specifically works for trans people, and especially medically vulnerable people.

By the end of Bandcamp Friday, we had exactly 100 sales, and I think 22 of them had actually downloaded the album. [Laughs] We were just like, oh, no one actually wants to hear it. It was amazing. It was so inspiring.

I’m guilty of not downloading it, but I did buy it, and listened to it on the Bandcamp app yesterday and today. The performances are sensational. They were recorded at Rockport Music, correct?

Yes, that’s right.

Whoever would have imagined that you could use Dvořák as a vehicle for social change?

Ives and Dvořák, right? Which is ripe for examination, actually, if we’re talking about American music and whiteness. I mean, ultimately we didn’t think that much about it; it was just like, let’s just get something out there. And also Chris Trapani’s piece… we thought of that whole program as being a folk program, and that’s worth engaging with more deeply at this time.

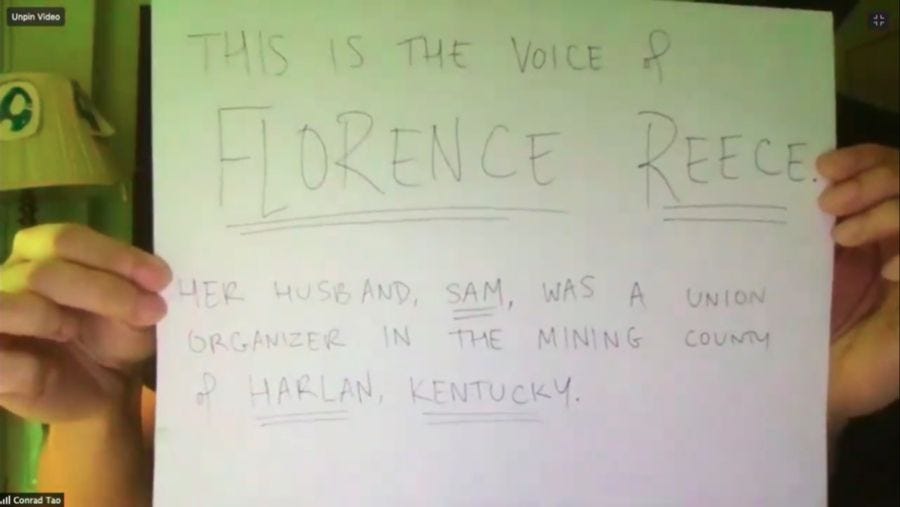

Coming around now to the Bang on the Can performance, a lot of terrific artists got in front of a camera and did personally meaningful things that felt good and were lovely to hear. And the community and camaraderie we always get out of a Bang on a Can event really has managed to survive the transition to this digital realm. But then you got up there and you did your thing with the Florence Reece recording, and the handwritten placards, and then the transition into the hip hop oriented segue – I recognized what it was, but not who it was, so the gesture was not lost, even if I couldn’t name the specifics – and then into a piece famously political, polemical, all the things you would ascribe to Frederic Rzewski’s music. How did you conceive your presentation of Which Side Are You On?

I asked them if I could play it. They asked me to play Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues at first, which I played on the recording I released last year. It’s a good piece – it’s a great piece – but after the protests began, I was like, we should do this instead. I’ve played this music for five years. Starting to play this program in 2015 was a really pivotal moment for me. It was the first time that I started thinking, maybe I can get some other points across with programming. My reluctance to do so in the past is… I don’t know, I guess I've not actually been that reluctant to do it in the past. I think about Unplay, the festival I did in 2013, and even on that festival, I was trying to engage with questions about canonization and activism.

But doing the program in 2015 – and spending time with Which Side especially, because Which Side also has this lengthy improvisation built into it – was a pivotal turning point, because it was the first time I started improvising in front of people, and the first time the music I was playing had explicit political content. So it just made sense—I mean, this is literally a tune about police violence, but it’s also about everything else. And it seems like, again, the thing that I’m excited by right now is that all of the usual cynical attempts at dividing struggle up are failing. This sort of really cynical tactic of like saying, “Oh, it’s not about me, I’m not going to take up space, I'm going to distance myself from it” – at the end of the day, that really is just about absolving yourself of responsibility or about trying to engage with this fiction that it’s not about you. It’s about all of us.

So this song, written by a white woman, coming out of the labor struggles of Harlan County, Kentucky, and having such a legacy in black civil rights struggles a few decades later, seemed important. It was an opportunity I didn’t want to pass up to really make sure all these threads were there. And the thing that’s really wonderful about being a performer and having programming as your canvas, as your medium… my definition of the basic unit of music is whatever the impulse is to draw a line between two points and say: There’s a connection. Programming to me seems like one of the most vibrant ways that you can activate that narrative-forming impulse, which is basically a human impulse to live and make sense of your life, and tell a story about the world without necessarily having to be prescriptive.

So in that performance, all I have to do is present various materials and provide some facts, and the narrative is drawn, right? I’m proud to be a storyteller, but I would like to do so in ways that are very tied to reality, and then that kind of just activates or draws people’s attention to the world outside. I’m not trying to be an escapist, you know? So that’s really the thinking behind that particular performance, and in general around programming.

At another point along your creative continuum, I wanted to ask you about what prompted the multimedia video piece you made for the ChamberQUEER online festival, ChamberQUEERantine, which was also in its way very beautiful and very powerful. Could you walk me through that piece?

The first thing I did in that realm was a commission from Guggenheim Works & Process. I really loved the opportunity to make a video for Works & Process as a way of composing, because it just happened to map onto what I was doing early on in the pandemic. I found myself playing music all the time, improvising all the time – improvising in the widest sense of the word – and making these videos spontaneously of just… things happening. Observation as music-making. Field recordings, essentially. Also, the iPhone’s microphones are really, really interesting and really beautiful and record in stereo, so there’s all this depth that you can engage with.

I made both of those videos primarily on my phone, with Videoleap, an app that I find really intuitive and that opens up all these lanes of engaging with musical material. Basically, the principle for both of those videos is that I want to make work right now that’s about right now. And I think that the nature of a pandemic, and the nature of this extraordinary, unpredictable time, and the nature of most of this work being consumed online means… well, permanence has never been very interesting to me, but it especially isn’t now. That sort of aspiration towards fixity is especially irrelevant now. So making these videos is a kind of documentation, but it’s also like you can stitch together your documentation. Two of my favorite films are in this vein. The film that really changed my life, actually, was Cameraperson. Have you seen it?

I haven’t. I know about it, and I’ve read extensively about it, but I have not yet watched it.

It’s gorgeous. It’s on Criterion. I highly recommend it. That method of construction, and the sort of essayistic narrative function of just using material, putting things in sequence, and allowing something to emerge—that’s so musical. I was really excited to have the visual dimension to engage with. And then from a creative standpoint, I was just trying to capture something about the feeling.

SS: What was the procession of vehicles you depicted in the newer video?

Solidarity honks. It was a march that started at Stonewall and went up to Union Square on June 2. There's been so many powerful sonic experiences, being in the protests, and the feeling of the solidarity honks was... I don't know, it’s really beautiful. It was the same feeling that I had when I read about the transit workers union declaring that they don’t work with the NYPD and they’re not going to transport arrestees—that’s the most amazing thing. That’s the most beautiful feeling. That’s the connective tissue of everything. That’s the sociality that makes music possible. For me, that is the thing I’m always trying to be faithful to, and the thing that I’m always trying to articulate something about. That’s where my fealties lie.

That’s right. Exactly. Now, not meaning at all to trivialize anything you just said – I mean this very sincerely – I actually love the sort of tactile autobiographical leitmotif of the crumpled plastic bag that carries through from the Guggenheim piece into the ChamberQUEER piece.

That started with this Piano Trio that I wrote last year for my trio. There was so much I was thinking about, and it was kind of, in retrospect, a little unclear, which is why that piece has no title, it’s just a piano trio, because there’s too many different elements in it. That trio begins with me improvising with the plastic bag while also playing a Charlie Patton recording. That was where it started.

Back then, I was thinking a lot about climate change, and I was thinking about the plastic bag bans put into place last year. I was also thinking about this Danish study from 2018 that revealed that our alternatives to plastic bags need to be reused so, so, so many times to balance out the environmental impact of production. A cotton tote bag – or worse, an organic cotton tote bag – when you factor in all forces of production, it has a worse impact on climate change. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t have a plastic bag ban, because plastic is suffocating our oceans. So the plastic bag feels to me like this really rich point of exploration into all of these seeming impossibilities that we find ourselves in.

It’s the same kind of paradox as finding out that streaming music online is as polluting, or maybe even more polluting, than manufacturing CDs ever was, because of the energy consumed by server farms and the greenhouse gases that get released into the environment. It’s one of those things you really have to struggle to get your head around.

And from the musicians’ angle, it actually encourages less active engagement with your music than piracy. So many people of my generation and beyond discovered themselves through piracy. It’s just a fact. And now you have idiots talking about the Internet Archive from exclusively this commercial standpoint… I don’t know, I get really sad about the internet getting swallowed up by profit motive.

In thinking about all of this, my final question to you was going to be, how do we take all of this and bring it with us when we begin to emerge from our cocoons and move back into the terrestrial sphere we once occupied. But that feels too big to be real – how do we do this? – and it puts too much of a burden on you to answer for your discipline or industry. So instead, I would simply ask: of all these things you’ve learned and observed over the last number of weeks of pandemic, protest, and beyond, what do you feel charged to bring back with you into the world when we’re able to meet and greet and touch one another again?

Well, just on a very immediate level, I want to put in concrete effort to program music by Black composers, because in the past it’s something that I've thought about, but have always found excuses to not engage more deeply with. I sat in on a recent Spektral Quartet listening session with George Lewis, and I was just like, there is a Black classical tradition, and there is a Black contemporary classical tradition. It would be so great to seriously engage with that, and do the field work necessary. So that’s one concrete thing that I’m taking with me into the future as a musician.

Really, I’m not thinking that much about my art in relation to everything, except that I’m trying to make work that feels honest. But I think those questions – what will we bring back to our sphere once we are able to, how should things be different – have to follow the enormous structural changes we’re asking for. And I am much more invested in that, at this point, than trying to see how we can fit things into the system as it currently exists, or how we can merely improve the system. I would rather entertain the question of, what alternatives can we imagine? At this point I’m more engaged in that. I’m still being practical, I’m still in communication with my manager, I’m still engaged in the day-to-day mechanics of a career, but the industry is in crisis.

We should really be looking towards the future in a much bigger way, not in this sort of incremental way. What would a musicians’ worker co-op look like? We never even entertain that idea. That’s not even in the realm of possibility in the current performing-arts structure. Neoliberalism teaches us that we’re all free-floating units that are selectively anointed with legitimacy and resources. Well, those resources are extremely inequitably distributed, and that legitimacy is starting to look really stupid right now. I don’t mean disrespect, but it’s starting to feel a little feckless. It would be much more interesting and productive to try to think beyond that.

Conrad Tao will present an online recital for the Tanglewood Music Festival on August 15 at 8pm; bso.org. He will be featured in a Digital Discovery Concert for National Sawdust on August 18 at 6pm; live.nationalsawdust.org.